Croatian

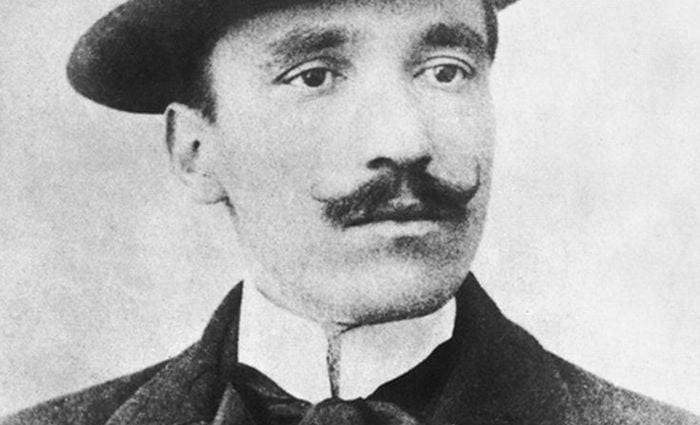

Antun Gustav Matos – (1873-1914)

Antun Gustav Matos was the son of a village schoolmaster. Shortly after his birth he was taken to Zagreb, where he received his early education. Later he went to Vienna and studied veterinary medicine, but as that failed to interest him he went to Prague. Being without a degree, he was drafted into the army as a private. He was sent to prison for violating some military rule, but escaped to Belgrade, where he played in the orchestra of the Royal Theatre. After many wanderings through Europe, he was pardoned and returned to Zagreb, where he worked as a journalist and teacher. There he did a great deal of miscellaneous writing. He died of cancer in 1914. Matos was a literary radical and a “Realist.” As critic, teacher, and novelist, he did more than any other prose writer to develop a native Croatian literature.

The Neighbor is one of his most vivid short stories. It is here published for the first time in English. The translation is by Ivan Mladineo, to whom thanks are due for permission to use it.

The Neighbor

He was very tired. While cooling himself at a window of his apartment on the second floor, his thoughts wandered afar. He had had to leave his country on account of debts. His family had turned him away, not without giving him the necessary expenses for his journey to America. He stopped off at Geneva and began gambling, winning at poker from the Slavic, especially the Bulgarian, students. When one of the students committed suicide, because of his losses, by drowning himself in the lake, Tkalac stopped gambling and conceived a happy thought: he would rent a larger apartment, buy a few mats and start giving lessons in fencing and later on in boxing (having learned this latter sport from a Parisian expert).

By means of the sword he made his way into the highest social circles, securing excellent recommendations, especially for Russia. After the wonderful match which placed him among the world champions, he made preparations to move to Paris. For the first time in his life he had managed to save money. The young, eccentric, cosmopolitan ladies, in particular, were paying him in a princely fashion.

He started paying off his debts in his native country. Everyone was won over by his behavior, which was undeniably good, being a heritage from a long line of heroic borderland officers, noblemen of Laudon s time. Like most of our frivolous men, he remained good at heart a childish, almost girlish, soul shining from his yellowish, eagle-like eyes; and a black, manly beard accentuated his rapacious profile, as it does in all our mountaineer descendants of hajduks and uskoks. Though he loved much, not a single woman did he really like, because at bottom he remained somewhat of a Don Quixote, dreaming of the ideal woman like all men who are brought up on the ideals of chivalry.

Read More about Istiklal Street and Taksim Square